At Mozilla, we use buildbot to coordinate performing builds, unit tests, performance tests, and l10n repacks across all of our build slaves.

There is a lot of activity on a project the size of Firefox, which means that the build slaves are kept pretty busy most of the time.

Unfortunately, like most software out there, our buildbot code has bugs in it. buildbot provides two ways of picking up new changes to code and configuration: 'buildbot restart' and 'buildbot reconfig'.

Restarting buildbot is the cleanest thing to do: it shuts down the existing buildbot process, and starts a new one once the original has shut down cleanly. The problem with restarting is that it interrupts any builds that are currently active.

The second option, 'reconfig', is usually a great way to pick up changes to buildbot code without interrupting existing builds. 'reconfig' is implemented by sending SIGHUP to the buildbot process, which triggers a python reload() of certain files.

This is where the problem starts.

Reloading a module basically re-initializes the module, including redefining any classes that are in the module...which is what you want, right? The whole reason you're reloading is to pick up changes to the code you have in the module!

So let's say you have a module, foo.py, with these classes:

class Foo(object):

def foo(self):

print "Foo.foo"

class Bar(Foo):

def foo(self):

print "Bar.foo"

Foo.foo(self)

and you're using it like this:

>>> import foo

>>> b = foo.Bar()

>>> b.foo()

Bar.foo

Foo.foo

Looks good! Now, let's do a reload, which is what buildbot does on a 'reconfig':

>>> reload(foo)

>>> b.foo()

Bar.foo

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "", line 1, in

File "/Users/catlee/test/foo.py", line 13, in foo

Foo.foo(self)

TypeError: unbound method foo() must be called with Foo instance as first argument (got Bar instance instead)

Whoops! What happened? The TypeError exception is complaining that Foo.foo must be called with an instance of Foo as the first argument.

(NB: we're calling the unbound method on the class here, not a bound method on the instance, which is why we need to pass in 'self' as the first argument. This is typical when calling your parent class)

But wait! Isn't Bar a sub-class of Foo? And why did this work before? Let's try this again, but let's watch what happens to Foo and Bar this time, using the

id() function:

>>> import foo

>>> b = foo.Bar()

>>> id(foo.Bar)

3217664

>>> reload(foo)

>>> id(foo.Bar)

3218592

(The id() function returns a unique identifier for objects in python; if two objects have the same id, then they refer to the same object)

The id's are different, which means that we get a new Bar class after we reload...I guess that makes sense. Take a look at our b object, which was created before the reload:

>>> b.__class__

>>> id(b.__class__)

3217664

So b is an instance of the

old Bar class, not the new one. Let's look deeper:

>>> b.__class__.__bases__

(,)

>>> id(b.__class__.__bases__[0])

3216336

>>> id(foo.Foo)

3218128

A ha! The old Bar's base class (Foo) is different than what's currently defined in the module. After we reloaded the foo module, the Foo class was redefined, which is presumably what we want. The unfortunate side effect of this is that any references by name to the class 'Foo' will pick up the new Foo class, including

code in methods of subclasses. There are probably other places where this has unexpected results, but for us, this is the biggest problem.

Reloading essentially breaks class inheritance for objects whose lifetime spans the reload. Using

super() in the normal way doesn't even work, since you usually refer to your instance's class by name:

class Bar(Foo):

def foo(self):

print "Bar.foo"

super(Bar, self).foo()

If you're using new-style classes, it looks like you can get around this by looking at your __class__ attribute:

class Bar(Foo):

def foo(self):

print "Bar.foo"

super(self.__class__, self).foo()

Buildbot isn't using new-style classes...yet...so we can't use super(). Another workaround I'm playing around with is to use the inspect module to get at the class hierarchy:

def get_parent(obj, n=1):

import inspect

return inspect.getmro(obj.__class__)[n]

class Bar(Foo):

def foo(self):

print "Bar.foo"

get_parent(self).foo(self)

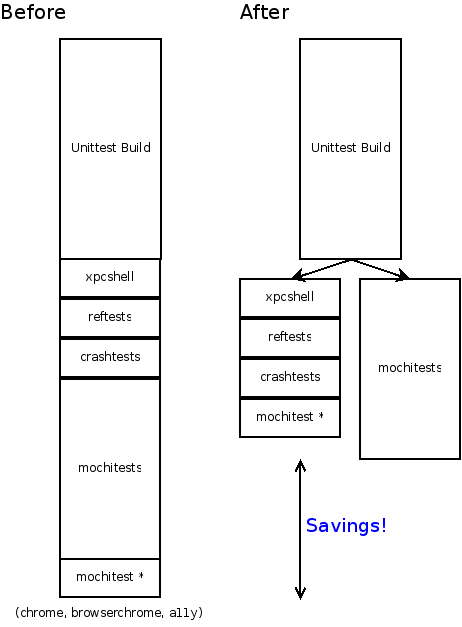

Splitting up the tests is a critical step towards reducing our end-to-end time, which is the total time elapsed between when a change is pushed into one of the source repositories, and when all of the results from that build are available. Up until now, you had to wait for all the test suites to be completed in sequence, which could take over an hour in total. Now that we can split the tests up, the wait time is determined by the longest test suite. The mochitest suite is currently the biggest chunk here, taking somewhere around 35 minutes to complete, and all of the other tests combined take around 20 minutes. One of the next steps for us to do is to look at splitting up the mochitests into smaller pieces.

For the time being, we will continue to run the existing unit tests on the same machine that is creating the build. This is so that we can make sure that running tests on the packaged builds is giving us the same results (there are already some known differences:

Splitting up the tests is a critical step towards reducing our end-to-end time, which is the total time elapsed between when a change is pushed into one of the source repositories, and when all of the results from that build are available. Up until now, you had to wait for all the test suites to be completed in sequence, which could take over an hour in total. Now that we can split the tests up, the wait time is determined by the longest test suite. The mochitest suite is currently the biggest chunk here, taking somewhere around 35 minutes to complete, and all of the other tests combined take around 20 minutes. One of the next steps for us to do is to look at splitting up the mochitests into smaller pieces.

For the time being, we will continue to run the existing unit tests on the same machine that is creating the build. This is so that we can make sure that running tests on the packaged builds is giving us the same results (there are already some known differences: